In one rare moment, Clay Eals is all but speechless.

An author and journalist, best known to the Valley as communication director for Encompass, Eals is the guy who makes his living with his words. He is also clearly (if briefly) overwhelmed, when he talks about all the things that a long-dead, almost-famous folk singer has given him in the last 20 years.

They were huge opportunities like the music to court his future wife, and a legitimate reason to travel the continent, meeting, interviewing, and once or twice going crab-fishing with some of the most beloved musicians in America. They were also simple truths, about the incredible generosity of people, how cruelly short life is, and the necessity of following your dreams.

His thoughts and stories about the singer, Steve Goodman, flow so swiftly, they pile up in his mind faster than he can get them out. Finally, he distills them down to one concept, gratitude. He leans over and pats the newly printed third edition of “Steve Goodman: Facing the Music, a Biography by Clay Eals,” then grins and whispers conspiratorially, “I got to do my some-day project!”

The book, an eight-year endeavor when it was first published in 2007, is an 800-page encyclopedia on the performer who people know primarily for his song “City of New Orleans,” made famous by Arlo Guthrie.

For Eals, though, seeing Goodman perform ruined him for all other musicians. “He was the best I’d ever seen,” Eals recalled. “He would make you laugh so hard…. and two minutes later, you’d be crying.”

A classmate of Goodman’s told Eals “He seemed to be more entertained than entertaining, and that, of course, is tremendously entertaining.”

As much as fans appreciated Goodman’s showmanship and wry humor, so did his fellow musicians respect his musical talents. Musician Tom Colwell, who will perform with Eals in a tribute to Goodman at 7 p.m., Sunday, Aug. 5 at The Nursery at Mount Si, remembered the one time he performed with Goodman, fondly.

“I had seen him perform at the Brown Palace, and was just blown away by the guy,” Colwell said. “His energy was like nothing you’ve ever seen.”

One night, while Colwell was performing at a bar called Somebody Else’s Troubles, Goodman walked in. He knew Goodman didn’t like want attention when he was in the audience, but decided to invite him up on stage, after he’d listened for a while.

Colwell introduced him as Joe Steel, a name that just came to him. Since Colwell was wearing his 12-string guitar, Goodman picked up his much-loved Fender six-string, and backed him up on several songs, including “City of New Orleans.”

“I’ve never heard music come out of that guitar like that before or since,” he said.

Although he was a phenomenon among musicians, and in the heart of the folk movement at the time, Goodman never achieved the fame that found Guthrie, or Goodman’s friend John Prine, or his protege, Jimmy Buffett.

“I know Steve Goodman’s an American iconic songwriter that has legions of followers all around,” said Nels Melgaard, owner of The Nursery at Mount Si. That was pretty much the total of Melgaard’s knowledge of Goodman when he took the opportunity, four years ago, to buy the evening on Steve Goodman, along with Eals’ book donated as an auction item for an Encompass fundraiser.

“He was a brilliant songwriter that died young,” Melgaard added.

At 20, Goodman was diagnosed with leukemia. It was 1969, and at that time, Eals said, the diagnosis was “a death sentence.” Instead of submitting to the disease, though, Goodman pursued experimental treatments at Memorial Sloane-Kettering Hospital in New York, and continued making music.

If he hadn’t, “we wouldn’t have ‘City of New Orleans,’ we wouldn’t have ‘A Dying Cub Fan’s Last Request,’ we wouldn’t have all these other great songs…” Eals said.

Goodman’s courage in facing his disease is what inspired Eals to write what he calls his life’s work.

“Clay’s energy around this thing is really unflagging… just remarkable,” said Colwell. “I think it’s because he’s developed a great respect for Steve’s commitment to be alive.”

Eals explains, “The book is, yes, about a musician, but it’s about how death is sitting on all of our shoulders… he didn’t have the luxury, shall we say, of forgetting about it, because he wasn’t supposed to live out another year.”

Goodman enjoyed a long remission from his disease, and lived 15 more years.

He died in 1984. Eals had seen him live only twice, but was moved by Goodman’s last album, particularly, the last song, “You Better Get It While You Can.”

Within a few years, he had started preliminary research. By 1999, he’d reduced his full-time job to half-time, to focus on interviewing more than 2,000 friends, classmates, and fans of Goodman. Four years later, he quit altogether. He worked on the book and spent time with his mother, who was placed in a nursing home across from his West Seattle home.

In an other four years, the book was done, and Eals accumulated 75 rejection letters before finding a publisher, ECW in Toronto. The first printing sold out in eight months.

His struggle to write the book has parallels to Goodman’s career, but without the tragic ending.

“Facing our mortality is a huge thing for all of us… and that’s the lesson of this book: We are not meant to be hermits in this life. We are meant to connect with and engage with and inspire people,” he said. “He was that, personified.”

Also, “I just think the guy deserved a book.”

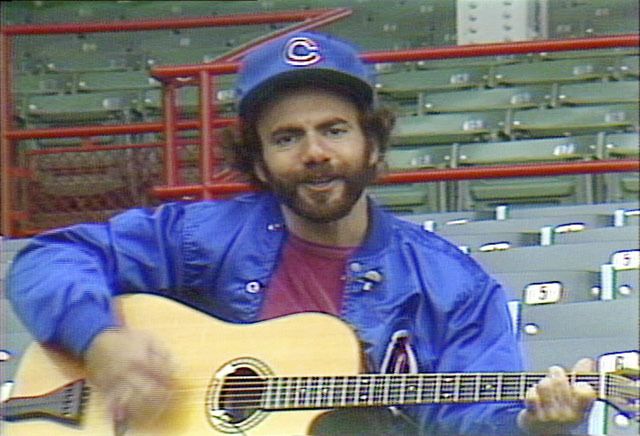

Above, Clay Eals, author of Steve Goodman: Facing the Music, and local spokesman for Encompass preschool; Below, the jacket for the third printing of Eals’ book on Goodman.