He grew up in the business, but John Groshell never had printer’s ink in his veins, like his father. Maybe seeing how many printers had lost a finger or two during their careers—one of the presses was called the hand-snapper, after all—is what cooled his enthusiasm, or the challenge of writing something every week. Certainly it wasn’t sporty enough for the future golf pro, teacher, and now owner of the Snoqualmie Falls Golf Course.

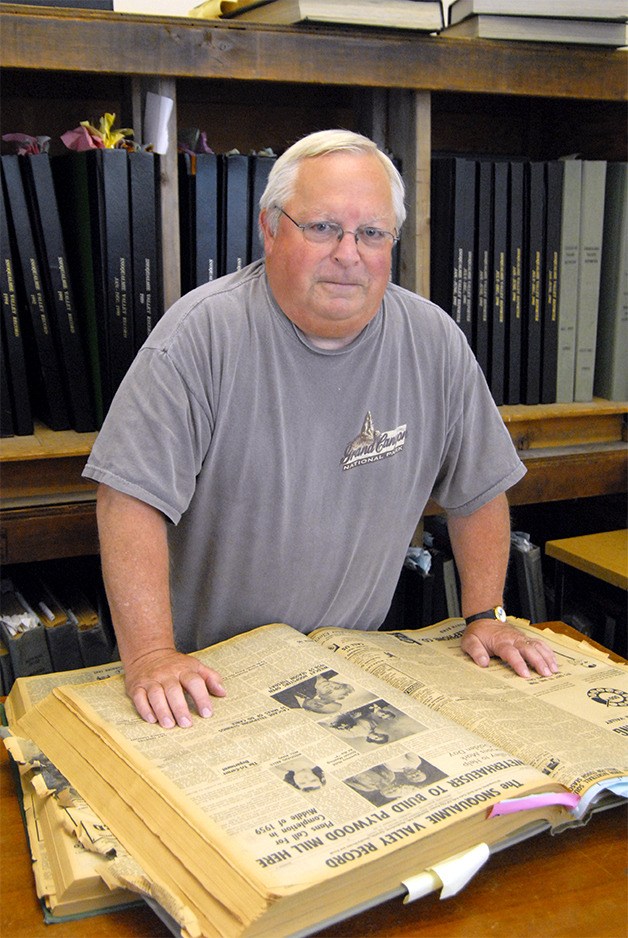

“If life didn’t involve a ball, something that you could throw, kick, shoot or bat, I didn’t care,” Groshell reminisced. He was visiting the Record office to talk about the days that he, his parents Ed Groshell and Charlotte Paul, and older brother Hiram, owned and operated the Snoqualmie Valley Record, from 1949 to 1961.

When his parents bought the paper and moved the family from Chicago to Snoqualmie in October, 1949, John was about 4 years old. Too young to recall much of the early days, at least without consulting his mother’s two memoirs on the subject, he would hang out in the office after school, deliver newspapers with his brother and sell subscriptions at times. An image of he and Hiram with a wagon full of papers to deliver made the cover of one printing of Paul’s “Minding Our Own Business.”

Boy at work

As he got bigger—“I always say I didn’t grow up, I just aged,” he jokes—John was put to work in the shop where he could. He scrubbed the leads and slugs (the metal pieces of type used to print) in harsh chemicals and sorted them into their cupboards. “That wasn’t much fun,” he said.

By the time he was 12, he was working the hand snapper.

Palms together and hingeing at his wrists, John opened and closed his hands with a clap to demonstrate how the machine worked, and why it was so appropriately named. “It was a press that went bam, bam, bam,” he said. “You’d put the blank paper in, and then it would close (clap) to print, then you’d take it out, and put in the next one.”

He developed nimble fingers and a nimble mind on this job.

“What you learned was don’t ever go back… because the press didn’t care. That’s why back in the old days, many printers were missing a finger or two, or three.”

Around that same time, he also started making the “pigs.” This job involved melting down all those leads and slugs that he’d cleaned, and pouring them into bricks to be fed into the Linotype. The machine melted the bricks, then shot the liquid metal into molds, assembled by the Linotype operator to create a line of type for the press.

Groshell never really worried about the hazards, though—“We had gloves that probably came up to here,” he said, gesturing to his elbow—and may even have preferred them to the other side of “community newspapering,” the reading and writing side.

“I worked, and I never minded working, but I was never into reading,” he admitted, including the newspaper. “I used to tell my mother that reading made me dizzy!”

Covering the news was all right, though. Besides himself and Hiram, the Record had lots of reporters in those days. “They had reporters in each town, there was a North Bend reporter, and Snoqualmie, and Carnation, Fall City, Duvall, and they would all contribute,” he said. The “news” was more than just listings of who visited whom and of good times being had by all, but those reports also had their place in the Record, he remembered. “I think people just really liked to see their names in the paper, and any accomplishments.”

Groshell, however, was an exception. He didn’t like to see his own name in the paper because that required him to write. Both he and Hiram had their own columns in the paper when they were in high school.

“My brother started and he had a column that was called the Hi Corner,” Groshell remembered. His own column, reviews of games and sports information was simply John’s Sports Shorts, and “…it was like pulling teeth getting me to write a column every week!”

Looking over one of his old pieces, about a college football game, he wondered out loud how he’d gotten an interview with one of the coaches. “My mother must have set that up for me,” he decided.

Even as a youngster, Groshell easily got his fill of publicity. He shakes his head remembering the long Christmas letters his parents used to send out, detailing the family’s exploits, and usually including a sweet, but embarrassing, photo of their sons.

“I would end up with kids bringing them to school and harassing the heck out of me,” he remembers. Still, he made it through high school, finishing out his senior year at Mount Si although his parents had by then sold the paper and divorced. Groshell went to WSU for a business degree, switched to teaching early on, and came back to the Valley to teach for five years, two at Snoqualmie Middle School, two at Tolt High School, and one at Mount Si. He loved teaching, he said, and sometimes wishes he’d never left the field, but school politics had discouraged him and the lure of sports was still strong. He played baseball and golf throughout high school, and continued golfing throughout college, so his career shift to golf pro was an easy one. After a year as a pro in Yakima, he came back to the Valley to buy a 20 percent share of Mount Si Golf Course, and eventually buy the entire business.

He was an independent kid, became a seasoned and popular teacher, and has a successful golf career and business today, but sometimes, he can still do without the publicity—and the Christmas cards. A few years ago, he recounts, a customer brought in one of his family’s old cards to show him. “Here was a picture of my brother and I walking in a field, and the caption on it was “Two little pumpkins in a field,” Groshell said with a sigh. “Now, fortunately that didn’t come out when I was in high school, but my employees saw it, and pretty soon I was Pumpkin. They still sometimes call me that.”