At first, you don’t recognize him. Then you realize that the smiling, bearded man in the red cloak and leopard pelt is actually a younger version of North Bend resident Rudy Edwards.

The image of a traditionally costumed Edwards is among the mementos of a two-year sojourn that he and wife Connie spent in the African kingdom of Swaziland in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Those memories were reawakened last month, sparked by the death of South African freedom fighter and statesman Nelson Mandela, at 95.

Edwards, who still knows a smattering of Zulu and Swasi words, experienced the color barrier for himself during the era when Mandela was an imprisoned champion of his people. Much later, Edwards witnessed South Africans of all races vote for the first time.

Going to Africa

In 1969, Rudy and Connie had joined the Peace Corps, and newly graduated from college, they went to the tiny, landlocked country of Swaziland.

That nation’s ruler, King Sobhuza II—the longest-reigning monarch on earth, ever since he was a baby in 1899—was transforming this forested, hilly land, bringing in Western-style education.

King “Sobhuza wanted Americans,” Edwards said. “He sent his kids to England and the U.S. to be educated.”

Majoring in biology at Jackson State University, Edwards had taken a number of teaching electives, knowing that he’d be in a classroom.

“We thought we were going to be in Kenya, or Tanzania.” But when a new program started in Swaziland, Edwards took it. He knew little about that place, so his professor at Jackson told him to read up on it. Swaziland is temperate and resembles the area around Spokane, and northern Idaho, with forestry, mining, and farming.

The English used there is British English, so Edwards got used to their way of pronouncing words like “aluminium” and “schedule.”

Edwards taught students from fifth grade through high school, and made many friends among the locals. Living and working as an African-American in Swaziland, he couldn’t help but sense and experience what was happening over the border in South Africa, right from the moment he arrived.

Since 1948, South Africa had pursued an official policy of Apartheid, or “apart-hood,” classifying and segregating inhabitants into four race groups: “white,” “black,” “colored” and “Indian,” with several sub-classifications. Most of the country’s inhabitants were black, but by 1970, they had lost their citizenship under the racially segregated system.

Some South African whites distrusted American Peace Corps visitors.

“In the Afrikaner papers, we were spies, trouble,” said Rudy. “They thought King Soubhuza was crazy.”

He and Connie “snuck in” to Swaziland via the Mozambique border.

“They didn’t want to cause a row, because we were black,” he said.

When they made their first visit to South Africa, the confusion of the Apartheid system quickly made itself apparent.

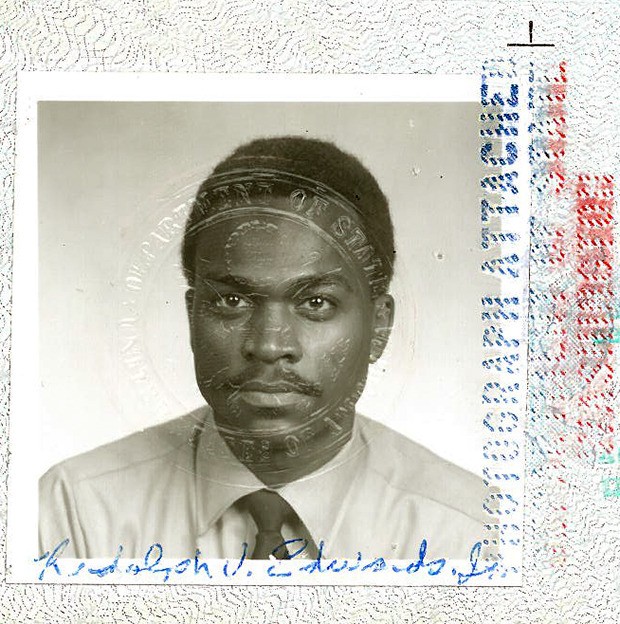

“The first time we got into trouble in South Africa is because of this,” said Edwards, holding up his old U.S. passport. “If you’ve got this, under their system, you’re white.”

At the border, Edwards listened as officials argued over which of their four race lines he belonged in.

He didn’t belong on the black African, or Bantu, line. Finally, “they made me get out of the Bantu line, where I was driving with friends, to get into the European line.” His African friends joked that they had to get out of the car, saying Rudy was white now.

“I knew I had to experience that, to feel what Apartheid was doing,” he said.

Teaching in Swaziland, Edwards remembers South Africans of all races coming over the border for casinos, moviehouses, and more illicit pleasures.

Edwards met exiles, people who couldn’t vote on account of the color of their skin. He met South Africans who were Jewish, Catholic, black and white, Afrikaner, and they often wanted to talk to him about being an American, and about getting the system changed.

Many said they didn’t like Apartheid, but “Some said it would never change,” he said.

While Edwards never met Mandela, he and Connie got to tour his house, and visit the church of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, an equally famous opponent of Apartheid.

By 1970, Mandela was already considered a people’s champion. Born into a Xhosa royal clan, Mandela was tall, handsome and well educated—he was the first of his family to go to school—and became an attorney.

Jailed for his political activities, Mandela was a controversial figure in his early career due to his leanings to the left. Communist freedom fighters were indeed part of the mix in opposition to the South African regime, and Edwards, on occasion, would encounter Marxist proponents. He had a simple way of refuting it—pointing to American aid and American bounty, in the form of wheat and other goods. “That came from Iowa, Oregon, Washington state,” he explained. “We produce the most. You can’t feed people with Marxism.”

End of the system

Edwards, who has lived in North Bend for 24 years, remembers when the Jim Crow era ended in his hometown of Laurel, Miss., population 18,000, during the 1960s. There were places blacks couldn’t go—“you wouldn’t go into a redneck bar”—but things were changing. An Eagle scout in his all-black Boy Scout troop, Ewards and another boy personally integrated the local forest service office, simply by asking for jobs. “I knew this day was coming,” the manager told them, then hired them both.

Yet South Africa under Apartheid was worse, says Rudy. At least in Mississippi, his family had for many years kept the right to own land.

In South Africa, people were fighting against the system, but in turn, “Afrikaners are shooting and killing you.”

“Even the worst day I had in Mississippi, growing up, was nothing like South Africa,” said Edwards, who returned with Connie after two years of teaching to pursue a master’s degree, and then a forestry career that led to the Valley.

Edwards’ African stay “made me appreciate what I have,” he said. “It made me a better person.”

Apartheid began to fall apart by the late 1980s, under pressure from without and within the country. Mandela, who had been jailed for life on conspiracy and sabotage charges, was released after 26 years in prison. He continued work for majority rule, which saw fruit in the first democratic elections for South Africa.

In April of 1994, Edwards experienced that moment. Living in the Valley, where he worked as a forest ranger, he invited School District 410 Superintendent Rich McCullough to accompany him to Seattle to witness the election.

At the King County Courthouse, “all these South Africans, of every color, were coming to vote from all over the Northwest,” said Edwards.

Voters assumed he was one of them. One woman asked him, in Zulu, “Where is Buthelezi?” referring to Mangosuthu Buthelezi, a South African Zulu leader and candidate in the elections.

“I don’t know,” said Edwards.

“You are an American, but you speak Zulu?” the woman asked. “Are you at the University of Washington?”

“No, North Bend, Washington,” Edwards replied.

Edwards holds two woven baskets, souvenirs from his Peace Corps days in Swaziland.

Part of the staff at the high school in Swaziland, where the Edwardses worked.

Connie Edwards at a day care center in Swaziland.

Connie Edwards sits with an African family, speaking in Zulu.

The Edwardses in traditional Swazi attire.

Swazi students keep cool under a tree.