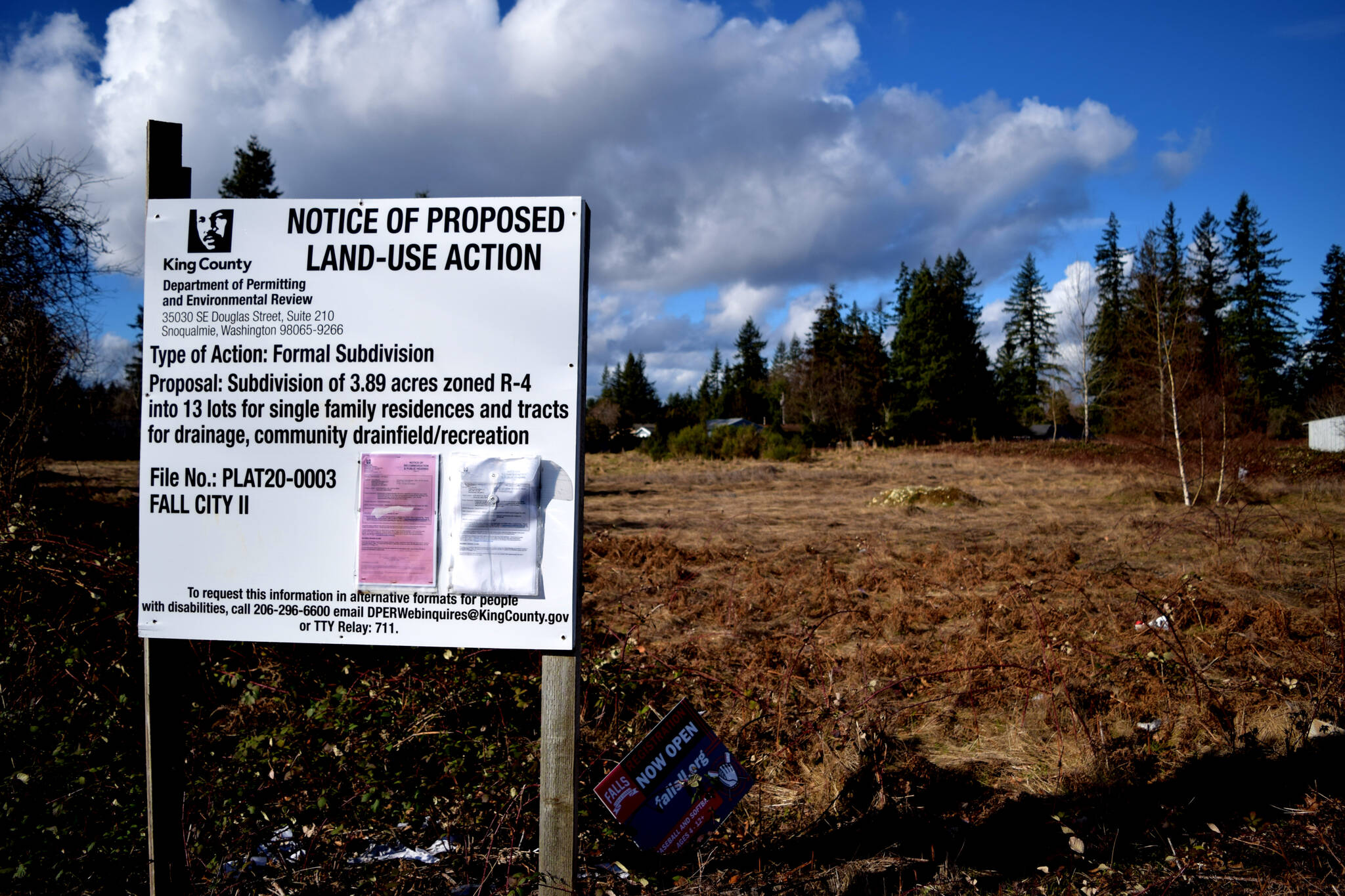

Right now, the lot west of Fall City Elementary school overlooking its baseball fields is mostly vacant, filled primarily by dead grass, blackberry bushes and a few evergreen trees visible in the distance.

Soon it could look much different. Plans to build 13 single-family homes on the property are already in motion, making it one of several lots in town being targeted for new single-family housing.

In total, there are six active subdivisions throughout town that — in addition to a recently completed subdivision — would add 121 new homes to Fall City over a few years.

It is an unprecedented level of growth that has raised questions about growth in rural areas and has left many residents worried Fall City’s character is being threatened.

The seven housing subdivisions are concentrated west of downtown and all have ties to Taylor Development, a Bellevue-based real estate developer. A representative of Taylor did not return a request seeking comment for this story.

One of those subdivisions, a 17-house project called Arlington Courts, has already been completed and sold. The remaining six all have active permits.

When finished, the new housing would raise Fall City’s population, which sits at just over 2,000 residents, by 300 people, if it follows the county average number of people per home.

While the developments are all compliant with local zoning codes, their existence has not been well received by town residents, who have referred to them as aggressive and exploitative.

Roughly 100 residents tuned in at a hearing held on the second of the seven subdivisions last month. Residents who spoke at the hearing argued the homes are out of character, serve no housing need in the community and put constraints on the already stretched local services and infrastructure, such as roads and emergency services.

“The public feels like we’re not being heard,” said Mike Suelzle, a resident and member of Fall City Sustainable Growth.

Fall City Sustainable Growth is a nonprofit group of town residents formed last month in response to the new housing developments. Suelzle emphasizes the group is not against growth, but has concerns about the pace of development and how it could change Fall City.

Their chief concerns are preserving the unique rural character of Fall City, preventing clustered homes more typical of suburban subdivisions and ensuring Fall City has sufficient infrastructure to handle its growth, Suelzle said.

Growth in rural areas

While community pushback to new housing projects is not uncommon, it usually happens in cities. The situation in Fall City has the added layer of it being a rural unincorporated area.

Since the adoption of the state’s Growth Management Act, the state has aimed to confine housing growth to city limits, mandating cities plan for housing growth targets. The goal is to limit urban sprawl into unincorporated areas and protect open spaces.

King County’s Comprehensive Plan, a long range planning document, aligns with this idea, defining Fall City as a rural town — one of only three places to receive that designation — and citing a desire to preserve its “rural character.”

“People come from all over King County to enjoy our town,” Rachel Shepard, another member of FCSG, said during a presentation. “There’s a reason we have our special designation. It’s rooted truly in preservation and conservation.”

Yet, while King County and Fall City residents state a desire to preserve rural character, there is little in King County’s building codes defining what that means.

And while Fall City is not required to grow, it is also not immune. There’s a massive regional housing shortage and land in Fall City is highly desirable. One of the Arlington Court houses, for example, sold for over $1.3 million just four months ago, according to Redfin, a Seattle-based real estate website.

Regardless of jurisdiction, a land’s developable rights ultimately boils down to its zoning, which means urban style development can occur in rural areas.

“Everything is driven by zoning,” said Ken Konigsmark, a former president of the Issaquah Alps Trails Club, who has spent much of his career working to preserve rural areas and open space. “There is no piece of land that doesn’t have some developable rights attached to it.”

Konigsmark points to the nearby Preston Industrial Park as an example. Since Preston had industrial zoning, it allowed developers decades ago to buy the land and permit development, even though it was in the rural area.

“There should be no industrial development in Preston. It’s out in the rural area,” he said. “[But] someone had a great idea that because there’s an I-90 interchange at Preston, we should put some industrial land out there. Once you do that you can’t take it back from the landowner unless you buy them out.”

Zoning in Fall City

Fall City residents had some foresight of its future growth, and during the town’s 1999 Subarea Planning process, they knocked down the number houses per acre in residential areas from eight to four, which is the current standard.

But King County’s code is limited on other requirements that are typical of rural communities, such as lot sizes or setbacks. The Taylor developments, for example, feature a cluster design, with homes close together and sharing a communal open space that is more typical of suburban subdivisions.

“There’s absolutely an opportunity to guide development in unincorporated areas better,” said King County Councilmember Sarah Perry, who represents northeast King County and Fall City on the council and chairs the Local Service and Land Use Committee.

“Developers can buy property. You can’t stop that,” she said. “What you can do is create some awareness around what constitutes rural character.”

Perry said she is closely monitoring the active developments in Fall City and looking at identifying ways to address density and rural character. Many of the residents she has spoken with are not opposed to the zoning of the new homes, she said, but have concerns over things like lot sizes and spacing.

As the county begins updating its 2024 comprehensive plan, which is a document that sets goals for the county over the next 20 years, Perry said she will be having many discussions about code changes to better serve rural areas.

“I’m wanting to protect that rural character. I want to dig down into what these codes look like and make sure we’re doing what we can to meet those needs,” she said.