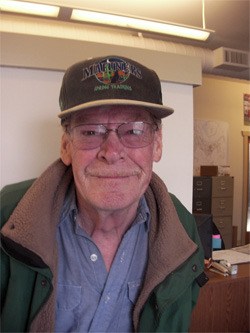

Lifelong Valley resident H.L. “Red” Engle put pen to paper and wrote his first short story nearly 30 years ago.

That piece, “The Lucky Raccoon,” about an unlikely pet named Bobby, was written for the pages of the Snoqualmie Valley Record.

Since then, Engle has dabbled in adventure stories, historical fiction and non-fiction, from sea tales to Westerns about lost Tolt River gold.

His writing grew out of his reading. Throughout his life, Engle devoured the stories of Louis L’Amour, Zane Grey, John Steinbeck and Jack London.

“After reading L’Amour, I thought, doggone it, maybe I could write a short Western,” Engle said.

At age 74, the Carnation resident, retired tree farm and railroad employee is still fascinated by history. He has drafted another manuscript, his first foray into prehistoric fiction.

Engle was inspired by the 1987 discovery of a cache of spearpoints in an East Wenatchee orchard. Anthropologists believe the stone implements are among the oldest evidence of human activity in this state.

“They thought maybe a bunch mammoth hunters had put a whole bunch of them together to honor some great hunter,” Engle said. “They don’t know. All they know is that they haven’t seen daylight for 11,000 years.”

Engle’s latest story, “The Track of the Mammoth,” ponders how prehistoric mammoth hunters may have shaped tribal cultures.

The following is an excerpt from his tale.

Figuring in “Red” Engle’s latest story, “Track of the Mammoth,” wooly mammoths once ranged across what is now Washington state.

Author’s Note:

It has been proven from artifacts that mammoth hunters were in Eastern Washington. A group of stone age people who lived in the Pacific Northwest, known as the old Cordilleran culture were living in the Columbia River Valley 11,000 years ago.

The Track of The Mammoth

Discovery of Snoqualmie Valley

By H.L. Engle

Within the dark cavern, amber blades of flame danced like puppets on a string, casting ghostly shadows on the rough stone interior.

The rugged Columbia Valley hunter brushed his long, black hair away from his brow and spoke to the men gathered around the cave’s fire hearth.

“We must prepare to move. The great ice has receded far to the North. Drought has come to the land and is forcing the game herds to the northwest. We must follow the animals if we are to survive. The meadows, lake and streams are disappearing. Our hunting territory is turning into a desert.”

The youthful and stalwart man, born with his right arm a hand longer than his left, was Sky, newly chosen leader of the family hunting group.

On a warm, late summer morning during the last years of mammoth hunting, Sky, his two brothers, and cousins, women, children and old ones, dressed in elkskin shirts and mammoth hides for footwear, headed west following the game animals, slowly moving over the land, blending with the landscape like the quail in the sagebrush.

They hope to find bigger game in the foothills: elk, bear, mountain sheep and perhaps the great shaggy ones with the curved white tusks and long noses.

After many days of wandering through the grass- and sage-covered bench-land, the family entered the foothills of the Cascade Range.

Skirting the edge of a beaver pond surrounded by clumps of willows and cottonwoods, Sky suddenly knelt and studied the ground. Motioning the others to halt and get down, he pointed to the tracks and whispered to his brother, Jumping Otter, “Fresh elk tracks, they’ve just left the pond.”

Testing the wind, Sky used sign language to tell his cousins to scout to the left of the tracks leading form the pond; his two brothers to the right; and he’d move up the center.

The five hunters crept stealthily among the trees, each armed with two seasoned alder spear shafts, tipped with four-inch flint points. The hunters used atlatls, spear-throwers, with rock weights tied on the bottom side for more thrust and accuracy.

As they topped a ridge beyond the trees, they spotted the herd of elk, four cows, two young bulls, and three yearlings grazing in a meadow.

Knowing that the elk hadn’t seen or scented them, the men wormed through the tall grass on hands and knees until they were within spear-throwing range. Sky made the sign that he would try for one of the bulls and for his brothers and cousins to throw at the cows.

The hunters laid their spears on the upper face of the atlatls and watched Sky for the signal to throw them. One of the bulls raised its head and looked about, stomped his front hoof, then continued grazing. At that instance, Sky gave the signal to hurl the spears. In a moment, two elk were down struggling in the grass. The hunters quickly killed them.

Sky was satisfied with the kill. The family would eat well and have skins for clothing. He told one of the men to go and bring the women and young ones to do the butchering.

The women finished cutting up the elk and had the meat bundled and ready to go back to camp, when suddenly from out of the woods on the far side of the meadow, a dozen men came charging, yelling and brandishing their weapons.

Knowing not what to make of them, Sky told everyone to stand fast and be ready to fight. A fierce-looking man who appeared to be their leader rushed to where Sky and his brothers were standing, pointed at the butchered elk and said, as he jammed his spear into the ground next to the bundles of meat, “I am Cle. Who are you… where did you come from? We have tracked these elk for two days. They should be ours. This is Kittitas, my clan’s hunting territory. We want the meat.”

Sky looked at the meat, then at Cle, and without fear, replied, “I am Sky. We have come from many suns to the east. We didn’t know this was your hunting ground. My family needs the meat and skins for clothes. What if we refuse to give it up?”

“Then my hunters will kill you and take it.”

Sky was not afraid to fight these men, or even to die, but if it came to a fight, his people would be outnumbered, and he had women, children and old ones to protect.

Sky turned to his brothers and cousins and, in a low voice, conferred with them for a moment, then said to Cle: “Would you accept half the meat and leave us be?”

Cle nodded, reached down and picked up a short stick, broke it in half, laid one half on the bundles of meat. The other he handed to his men. His hunters grunted their approval.

Sky and his family stayed at their camp a few days, while the women, using the brains of elk, scraped, cleaned and softened the hides. As soon as the cleaning was completed, Sky thought it best to be moving on. They were being closely watched by Cle and his hunters, and he didn’t trust them.

The morning the family prepared to travel, Sky’s mother sadly told him, “Your father, White Fox, died during the night.”

A shadow of grief fell across Sky’s face. He put his long arm around his aging mother and said, with a soft voice, “I am sorry. He was old. He lived many summers, many snows. He was a good father and provider and had been a good leader of our family. I wish to do as well. We will miss him greatly.”

Sky and his brothers, with pointed sticks and scrapers, dug a shallow grave at the edge of the camp site and laid the body of White Fox within. As Sky placed his father’s favorite spear and knife in the grave, Jumping Otter asked, “Should we leave food?”

Sky replied with tears in his eyes. “No, the bears and wolves would smell it and dig at the grave.”

The family gathered around and Sky asked the God of the Mountains to safely guide his father to the spirit world.

As the cool breeze softly swayed the tall pines and firs, the men covered the grave with soil and laid heavy stones on top to keep out the animals.

Farther into the foothills wandered the band of hunters, camping and hunting, pushing on into the main range of the central Cascade Mountains.

While scouting a well-traveled game trail, Sky noticed where branches had been ripped from trees. This in itself as not unusual, he reasoned. Windstorms do it, and he’d watched deer and elk do it with their antlers. But some of these branches had been broken off nearly twenty feet above the ground, with large scuff marks and long pieces of bark torn loose and shredded.

Sky pointed and said to the men, “If bears had broken these branches, there would be claw marks on the trunks.”

“Only one animal is tall enough to reach that high and do as much damage: a woolly mammoth.”

From discovering the sign, Sky quickened with anticipation. Turning to his trail mates, he said, “We have not seen the great shaggy ones for many summers. If we could find and kill one, our family could have a feast and meet for many days, and robes for the coming winter.”

The sun was beginning to set below the mountain peaks, sending its last golden rays of the day down the green and blue canyons and draws. The hunters rounded a curve in the game trail and came upon a wide, damp and mossy spot.

Sky suddenly halted the group and pointed at the soft ground.

“Look!” he yelled, as he squatted and ran his hand across the huge, round impressions. “Never have I seen such huge tracks. They’re four hands wide. See the imprints of the three crescent-shaped toes.”

Sky said to the men as they studied the immense tracks, “The beast that made these must be very old with great height. His tracks point toward the high mountains. We must followed him.

Jumping Otter frowned. “His sign is many days old. We should return to the foothills where the hunting is good.”

Sky sternly replied, “I know his sign is old, but he is also old and will not travel fast. He will stop often to eat and rest.”

Sky pointed toward the high peaks.

“Perhaps he will show us a way through the mountains. We cannot go back to where we’re not welcome. Cle and his hunters may attack us. And we can’t stay here, winter comes early in the mountains. We have to move on; we’ll follow the sign of the woolly one.”

Sky knew, as the others did, that hunting the woolly mammoth was dangerous. He’d seen hunters trampled to death and others impaled on their massive tusks. But still, he loved the thrill of the hunt.

For three suns Sky and his family followed the sign of the mammoth—through rugged canyons, over timbered ridges, across alpine meadows and snow fields.

During the morning of the fourth sun, the hunters reached the west side of the mountains. Coming out onto a high ridge overlooking a lush, green valley, stretching wide and as far as the eye could see.

Far below, three rivers flowed onto a broad plain like giant green snakes, twisting and bending through stands of conifer and maple.

The hunters slowly picked their way down the long ridge to the floor of the valley. The mammoth’s tracks led to the south river, then on down the stream along the north bank to where the river merged with a larger stream flowing west.

Sky noted the abundance of game in the pristine forest—deer, elk, bear, mountain goat and many schools of fish in the river. But most of all, he noticed that the huge tracks were fresher.

As the family group headed downstream, Sky told everyone, “Be alert and watchful. We could suddenly come upon the mammoth and he might attack us.”

Sky gestured toward the surrounding hills.

“This valley is beautiful is a bountiful land with much game, and no sign of any other people. That is good.”

Jumping Otter eyed his brother, then smiled.

“Yes, the valley is illahee, a good land.”

Suddenly, the trackers heard a deep rumble. Sky halted the group and they all listened for a moment. Not knowing what to make of it, the hunters left the mammoth’s tracks to investigate the strange sound.

Carefully following the river around the face of a low hill, the hunters saw that the river split into two channels, one on each side of a huge rock in the middle of the stream, and spilled over a high, sheer rock cliff. The thundering falls were higher than two fir trees.

Kneeling at the edge of the cliff, the family looked over the falls into the vast, green expanse of the lower valley. The band of hunters felt the vibration as tons of water cascaded over the cliff into a deep gorge, crashing into the river and rocks far below. They were entranced by the awesome sight, and trembled with fear. It was as if the Great Spirit was shaking the earth.

Peering between the rising clouds of mist that vaporized like ghostly blankets of fog on a warm summer morning, Sky became like a stone, as though he were lightning struck. He pointed a trembling hand and said to his companions in a low voice, “Look… it is he… the great woolly one. He is the biggest mammoth I’ve ever seen. Can’t you see him? There, standing on a gravel bar, like a bay-colored block of granite with curved white tusks. Even from here he looks like a giant, taller than two men and his tusks at least nine feet long?”

Jumping Otter asked with wonder as he stared wide-eyed at the beast, “How did he get down below the Falls?”

Sky replied, “He must’ve crossed the river upstream and taken a secret trail around the bluff.”

“Are we going down the hill to try and kill him?”

“No, I think not. We will not hurt him.”

“Why not?” Jumping Otter demanded. “You told us our family needed fat meat and robes for winter.

Sky frowned. “I know, I was anxious to kill a mammoth, but now I have lost the desire to kill him. He may be the last of his kind. This valley has plenty of game for meat and firs without killing the great one.

“The mountain gods wanted the great mammoth to lead us to this valley,” Sky said, as he looked toward the mountains. “See the high mountain guarding the head of the valley on its peak? It has the face of Snoqualm, the Moon, Chief of the Heavens. We will name the valley The Valley of the Moon, and it will be our home, too. For the rest of our days.”

After watching the great shaggy one a little longer, the family continued down the hill, following the river, looking for a good place to make camp. They finally came to a place with level ground near where a smaller river flowed into the larger one that, many centuries later, would be known as the Snoqualmie River.