When the coronavirus pandemic closed businesses across the state, economists were initially optimistic there would be a quick recovery. But as infection rates again increase, and an economic reopening stalls, those hopes are gone.

A quick economic recovery, known shorthand as a “V-shaped” recovery, isn’t happening, said Anneliese Vance-Sherman, an economist with the Washington State Employment Security Department. Instead, the recovery will be longer and likely come in waves. She’s expecting a U-shaped recovery, at best.

“We were hopeful that everything would bounce right back, and it’s gone on long enough that we’re already out of that territory,” Vance-Sherman said.

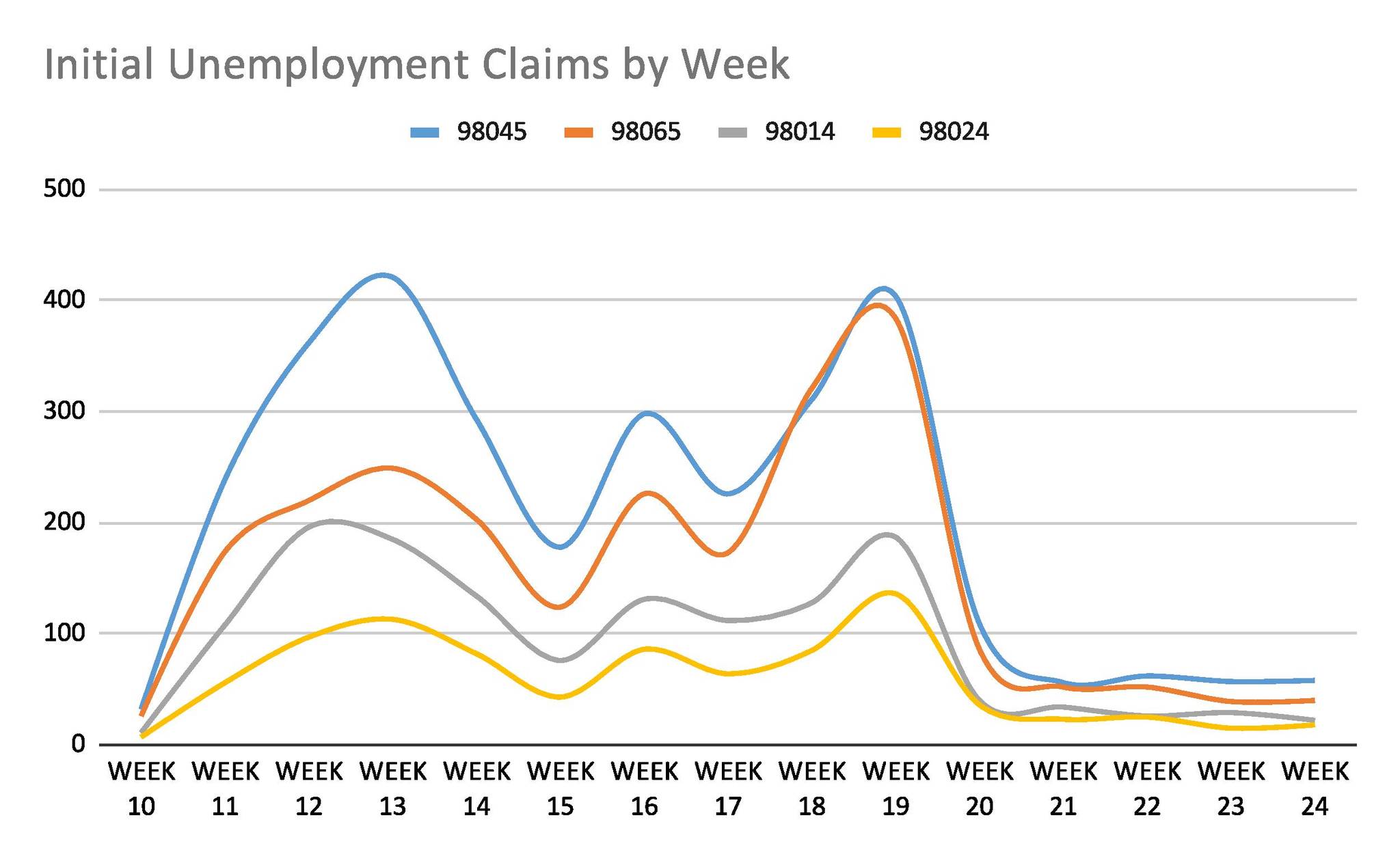

The Snoqualmie Valley is no exception. Unemployment statistics for four ZIP codes in the valley show a massive increase in unemployment claims near the beginning of the outbreak in early March. For the ZIP code 98045, initial unemployment claims jumped from 32 the week of March 2, to 239 the following week.

The story was the same in 98065, which contains the city of Snoqualmie. Unemployment increased from 26 new claims to 174 during the same weeks. In 98024, Fall City and the surrounding area, claims increased from seven to 56. And in 98014, Carnation, new unemployment claims increased from 11 to 108 between the weeks of March 2 and March 9.

New and continued claims trailed off over the following weeks before again spiking during the last weeks of April, when Pandemic Unemployment Assistance was opened up to self-employed workers and others.

They again began to decline in the following weeks. It’s unclear how much of this is due to the state identifying and addressing fraud, but Vance-Sherman said numbers in the valley are similar to what they’re seeing across the state. The state paid up to $650 million in fraudulent claims.

Still, disparities exist between white collar workers who can telecommute and retail workers and other blue collar employees, particularly those in low-paying retail and service jobs.

North Bend relies heavily on service jobs. In 2017, there were more than 2,100 service and retail jobs in the city, according to a report by Community Attributes Inc. (CAI). It was by far the largest sector. The report noted that many of the jobs in retail are relatively low paying, and many do not pay enough for workers to afford to live in the city.

About 26 percent of North Bend workers live in North Bend, Snoqualmie or the surrounding area.

In neighboring Snoqualmie, Mayor Matt Larson said the city is expecting to see drops in sales tax revenue to the tune of 30 percent for large retailers. But some small businesses have lost up to 75 percent of their sales.

Small cities are vulnerable to economic downturns. North Bend continued losing jobs from 2009 to 2016, stemming from the last recession.

It’s unclear how the coronavirus recession will impact the valley. Vance-Sherman said impacts to rural parts of the state will vary by region. For example, Yakima County is seeing a large increase in COVID-19 cases because of a large agricultural workforce.

Other areas that rely on tourism, such as San Juan County, will likely take a hit as fewer people go on vacation.

For businesses not deemed essential, their economic vitality will depend heavily on when and how the state allows King County to reopen, and whether people return to shop.

King County recently entered Phase 2 of Gov. Jay Inslee’s plan to reopen the state’s economy. But with cases rising, Inslee has hinted at returning to previous phases — and their restrictions on movement and businesses. Larson said that would be devastating for local businesses.

King County Councilmember Kathy Lambert has been thinking about small businesses in her district too. The council passed an ordinance that allows businesses with parking lots, street parking or other outdoor space to utilize it for sales.

Keeping small businesses afloat in small cities is important, as many are specialty businesses that provide a certain set of services or goods.

“In the smaller cities, it takes a lot of little stores,” Lambert said.

She’s not sure how they will fare if the county isn’t allowed to progress in reopening stages. Most retail businesses are capped at or under one-third of their maximum occupancy.

“A lot of people have been trying to hang on because they thought we would all be in stage three soon,” Lambert said.

Vance-Sherman said even if businesses are open, people may have formed new habits while quarantining. She has questions such as: Are people going to feel safe in stores? How will businesses adapt?

Some businesses may invest in new technologies, reducing their human payroll in favor of machines that reduce face-to-face interaction.

“I do expect to see a lot of innovation, a lot of technology,” Vance-Sherman said. “It’s going to be very different depending on the business and their niche.”

Nationwide, the amount of jobs being recovered is still well below the pre-pandemic baseline. The Economic Policy Institute states there were 4.8 million jobs recovered in June on top of 2.7 million in May. But so many jobs were lost in March and April that the country is still 14.7 million jobs below where it was in February.

The week of June 29 marked “the 15th week in a row that unemployment claims have been more than twice the worst week of the Great Recession,” the authors state.

There’s also worries about what will happen at the end of July. Many people collecting state unemployment have also been receiving $600 a week as part of the federal CARES act. Unless extended by Congress, it will expire at the end of this month.

The Economic Policy Institute writes that with the federal money running out, June’s labor market may be “the best we can expect for a while.”

“I think it will be a long time before we see a substantial increase (in jobs),” Vance-Sherman said.

And it’s not just jobs that are impacted, but housing too. Gov. Inslee implemented a coronavirus-related moratorium on evictions in March. Since then, it has been extended through Aug. 1.

In 2018, a report from the Regional Affordable Housing Task Force found that in King County, many renters were cost-burdened, or spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent. Around 56 percent of Black households, 50 percent of Hispanic households and 35 percent of white households were cost-burdened.