Snoqualmie Valley’s latest shake on May 25 raises the possibility of an even bigger earthquake on the horizon.

This is the second quake to hit the Valley in less than six months. A magnitude 2.9 earthquake occurred on Christmas eve of 2009 and was centered on Snoqualmie. That quake’s epicenter was about 10 miles deep, and, like the four-mile deep Carnation quake, was considered a shallow quake. By comparison, the 2001 Nisqually earthquake, felt around the Northwest, was about 32 miles deep.

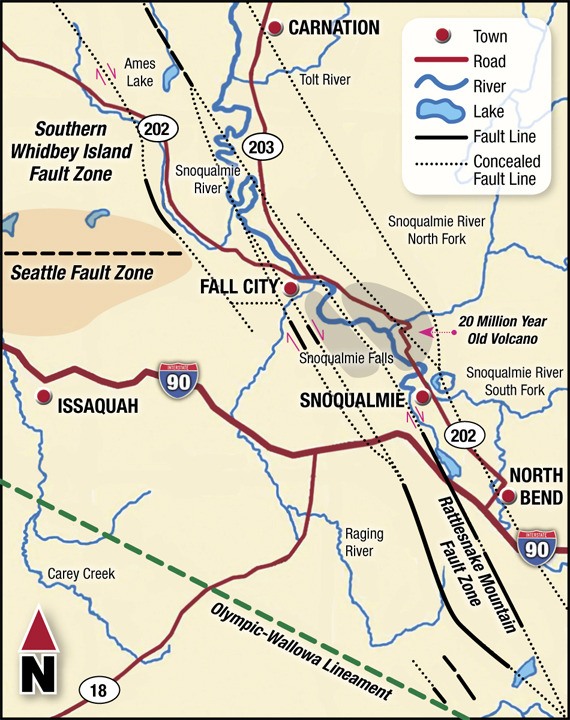

While minor, last week’s quake also shows that the ground beneath the Valley is far from still. Three faults converge beneath the Snoqualmie River.

Fault lines

About 10 years ago, geologists working on Bainbridge Island began looking at new images of the region and found traces of surface offsets, or topographic features changed by fault lines.

“It became clear that there was a history of movement on a couple of large fault lines, that in the future, could happen again,” said John Bethel, geologist for King County Department of Natural Resources.

One fault was traced from Bainbridge through downtown Seattle, across Lake Washington and to the south end of Lake Sammamish. Studies are still being done to see how much further the fault goes east.

Similarly, the South Whidbey Island fault starts on the south end of the island and cuts east.

Joe Dokavich, lead mapping geologist for the Washington Department of Natural Resources, is leading the release of maps showing that the southern Whidbey Island fault extends much farther south and east than once believed. The fault connects to the Rattlesnake Mountain fault zone in the Snoqualmie Valley.

Dokavich’s team has determined that the Rattlesnake Mountain fault zone extends from North Bend through the Snoqualmie River Valley to Fall City and Carnation. Dokavich believes the Rattlesnake Mountain fault is a continuation of the South Whidbey Island fault.

According to DNR, the North Bend fault zone is four miles wide and consists of a series of parallel faults, strands that follow the valley edges and determine the location of the Snoqaulmie River.

The Seattle fault, a shallow surface fault that causes ground shifts, does not extend to the Rattlesnake Mountain fault zone near Fall City.

Snoqualmie’s recent earthquake is typical of small, shallow quakes that occur in the area, the result of stresses in the earth’s upper crust, Bethel said.

However, scientists may not know all of the fault systems in the region that produce large quakes.

“There could easily be faults that could cause damaging earthquakes anywhere in the Pacific Northwest,” he said. “There is no reason to think you couldn’t have a large, damaging earthquake in the upper Snoqualmie Valley. We just don’t know when.”

No one has a foolproof way to predict when earthquakes happen. The best that scientists can do now is identify faults where earthquakes occur, and how often.

Studies by state and federal geologists in the next few years will help determine the frequency and severity of earthquakes along Washington’s fault zones.