Bravely voyaging into uncharted waters is the common thread that links North Bend resident Dave Olson’s life to three generations of his family.

Olson explores how he, his father, the Reverend Roy Olson, his brother Ken, and his daughter Jenifer each took paths less traveled, and changed lives around them, in his new book, part memoir, part anthology.

“Bonded by Water” publishes this Friday, June 27. A book release party is 7 p.m. Friday at the Meadowbrook Farm Interpretive Center in North Bend.

The public is invited to a slideshow and presentation by Olson on the book, which has taken him more than eight years to write.

The book’s genesis happened when a friend inspired Olson, 85, to pen his memoirs.

“I soon got bored with me,” he said. But, pondering his life, Olson remembered his father, “who always thought the first 50 years of his life were worth a book.” Then there was his brother, a fishing boat captain turned youth-ministry boat pioneer, and his late daughter, Jenifer.

“They went down roads less traveled,” Olson said. “All three were doing things that were away from what people normally do with their lives. They left legacies, in their own ways.

“How many of us are remembered for anything past the memorial service, if we’re remembered at all?” he added. “I’m the only survivor, the common thread that has the stories and writings. It dawned on me, if I don’t tell these stories, who will?

Minnesota days

Dave’s father, Roy Olson, was a Minnesota Lutheran minister who found himself drawn to the Alaskan coast. Fresh out of seminary, the Reverend Roy spent an intern year as chaplain to the seaman’s mission at Ketchikan, Alaska, preaching to mostly Norwegian immigrant fishermen.

“Dad never forgot it,” Olson said. Roy returned to Minnesota, got married, got a suburban church of his own on the south side of Minneapolis, and got involved in civic life. He was an avid fisherman on Minnesota’s lakes.

One story Olson relates is how Roy helped clean up the seedy part of Minneapolis.

That city’s downtown ministers grew tired of the bookies, burlesque houses and other dens of vice just a few blocks from their doors. So Roy and another minister removed their collars, donned some old clothes, and decided to document things first-hand.

“They went to both burlesque shows, checked in with a couple of bookies, and walked into one house of prostitution, and talked to the madam for a minute,” Olson said.

When the downtown ministers took their concerns before the city mayor in a public meeting, he challenged them to back up their complaining with evidence.

“’Who’s seen it? Give me some concrete examples?’” Olson relates the mayor’s reaction. “As the story goes, the ministers looked at each other and said nothing. My dad said the mayor was like the cat who’s swallowed the mouse. Up went my dad’s hand. ‘Mr. Mayor, I’ve seen it all.’ He related the whole nine yards, with the reporters taking the story. That was the end of the burlesque shows.”

Reverend Roy Olson holds a pike caught in a Minnesota lake in the late 1930s.

North to Alaska

By the early 1940s, Roy was having health problems. Doctors found tumors in his bladder, and warned that he might have only a few years left. Find a smaller church, they told him, and take the pressure off.

Through a bishop friend, he learned that Ketchikan needed a minister. ‘Do you want to do it?’ the bishop asked.

“My dad was a guy who could make up his mind to something faster than you’d blink an eye,” Olson said. “He came home that night to tell our family.” Two months later, they were on the Empire Builder railroad to the Pacific coast, and for 13-year-old Dave, it was the beginning of a grand adventure.

“I loved it. It was the best thing that ever happened to our family. Everybody agreed to that,” he said.

“When I first saw the ocean, I can remember to this day. When we got on the Princess Louise to head to Alaska, I took a smell of it. I saw it. I observed it on the way up. By the time we reached Ketchikan, I was in a love affair.”

With World War II under way, many young men were at war. Alaska’s coastal industries were hiring, and Olson got his first deckhand job when he was 15. He worked two summers on a tugboat towing log rafts from the coastal camps to Ketchikan’s mills, then graduated to the fishing industry.

“Where else could I go and make $200 a month and room and board as a 17-year-old kid?”

Olson crewed fishing boats for old Norwegian captains and latter-day Vikings.

“These guys were, in their own quaint ways, like fathers,” he said. “They worked me hard.”

Olson learned a lot, and by age 21, was captaining his own boat. He’d go up for the summer season, earned his pay, then shipped south in the fall to attend college at Pacific Lutheran University in Parkland.

In 1952, Olson completed college. The Korean War was in full swing.

“Our Marines and Army were up in northern Korea,” Olson said. The Red Chinese army had crossed the Yalu. “You were going in the service, no matter what.” His dream of becoming an airplane pilot went bust when they told him his depth perception was too poor. Another avenue, Navy ROTC, was full.

“Then I got lucky,” Olson said. “One day, the dean tapped me on the shoulder and said there was a gentleman coming to the campus to his office. He would be bringing together other young men in the senior class who would perhaps be of interest to this gentleman,” who, Olson discovered, was from the Central Intelligence Agency.

China coast intel

“When I walked into that room, I was looking at the cream of the crop of the senior class. The top athletes, top politicians…. all the wheels were there. I looked at my record, and said, ‘You don’t belong here, you might as well forget it. But I stayed.”

The CIA man’s form included a key question: Employment history.

“My employment history was going to work as a deckhand when I was turning 16 and running a fishing boat when I was 21.”

Olson watched as classmate after classmate entered the dean’s office, then quickly left.

“Next thing I knew, I found myself all alone.” The CIA man shook his hand and asked him all about his experiences on the boats. When he finished, he was told that if he passed muster with training classes in Washington, D.C., a job was waiting for him—in the offshore islands near China.

“There were good reasons why we were there,” he said. “Our soldiers were up there fighting the communists in North Korea. At the same time, the communists had kicked the nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek back to Taiwan.” But in the islands strung along the China coasts were warlords faithful to the nationalists.

“The ideas was that any Chinese communist forces that could be preoccupied on the coasts, because they thought the nationalists might come back,” would relieve pressure in Korea. So, the United States supported these coastal forces covertly. Olson’s job was to help these groups, arming and upgrading their junks.

“These warlords had people who had been engaged in piracy for thousands of years. They were pretty good at it,” he said. “Our job was to raise hell on the China coast.”

Olson, at 23, spent a year on an island base. A month after he left, the Chinese had enough, and leveled the place with Russian-provided bombers. Olson’s guerillas were evacuated by the U.S. 7th Fleet, and would up as conscripted labor in Taiwan, he said.

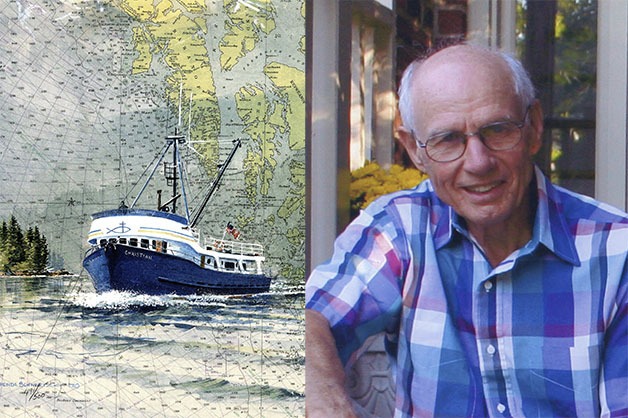

Rev. Ken Olson with the M/V Christian cruise boat;

The Christian

Olson also relates the story of his brother, Reverend Ken Olson, who started his career, like him, on the Alaskan fishing boats.

Ken learned the trolling business, and then decided to buy his own boat. So, with help from his father, he bought his own boat, and took off from Tacoma for the northern fishing grounds at age 20. Later, a younger brother, age 12, went with him to fish the Bering Sea.

“I get tired of modern mothers,” says Olson, who marvels at how his mother let her two sons, one age 20, the other 12, go to sea. “She never heard from them, maybe a letter or two, for three months. And it didn’t faze her. It was a different age.”

After fishing, and service in the Marine Corps, Ken became a Lutheran preacher like his father, and made his legacy on the waters of Puget Sound.

His first ministry was on Whidbey Island, where he helped with Bible camp.

“The kids, he found, were not that at ease with the strictures of Bible camp,” Olson said. “He got the bright idea that maybe they could get themselves a couple of runabouts, and give them a different idea of what the magic of life was about by taking them out on the San Juans.”

That idea was so successful that Ken decided they needed a bigger boat, so he connected with friends at the Nichols Brothers yard at Freeland, Wash, to build a 68-foot mini-cruise ship, the Christian, that is pictured on the cover of Olson’s book.

It voyaged with many youth groups, church groups and charters. Passengers learned a lot on those journeys, “because they did the crewing on the boat,” Olson said. “You’ll find interesting stories in the book about that, all collected by other people.”

Jenifer Olson, Dave’s outdoorsy daughter, died in a climbing accident in 1982.

Tragedy strikes

Telling the story of his daughter, Jenifer, and her tragic death, was the last the part of the book he wrote, and the hardest.

In the early 1980s, Olson and his family were living in California, and he became interested in rock climbing.

Jenifer, nicknamed Jef by the family, was in her 20s, and started climbing with her father and his fellow enthusiasts.

“She was a good athlete, a skier, a hiker, an outdoor kind of girl,” Olson said. Besides her skiing, she was involved in churches, and worked with teens.

One day, Olson invited her to climb the 13,000-foot Bear Creek Spire in the northern Sierras.

“She knew the ropes,” he said.

On the cliff, he was the third person on the rope, and Jenifer brought up the rear.

“I left her on this ledge, where she was sitting on a beautiful day, admiring the view and looking out over the whole scene,” Olson said. “Somehow, or other, I touched a boulder. And it took off. She was down below, 150 feet. I hollered like crazy.

“If she had stayed where she was, she would have been safe. If she had gone to the right, she would have been safe. She went left. It hit her square. She was killed instantly.”

After Jef’s death, the family picked up the pieces. Olson struggles to this day with reliving this moment. But he knew it was part of the family story.

“I have a hard time getting through talking about it,” he said. “Maybe I’m getting there.”

Valley friends may be interested to hear Olson’s family history. He and his wife Betty have lived in the Valley since 1996.

“Betty and I have been very fortunate in our life here.” They’ve been involved with local food banks and churches, and Olson was a site steward for the Mount Si Natural Resources Conservation Area.

The lesson he drew from his family’s adventures was that they weren’t afraid to break new ground.

“When they saw open doors, they walked through them. They didn’t hesitate. When they saw possibilities, they took them.

“Of all those preachers back in Minneapolis, my old man was the one who went down to see what was there,” he added. “That was my father!

“Sometimes, I see in the modern day, there is a tremendous urge to live safer lives, without risk. I’m not sure that’s altogether wise.”

• “Bonded by Water” is 305 pages, with 62 photos four maps and a dozen original poems. Learn more about the book at www.bondedbywater.com.