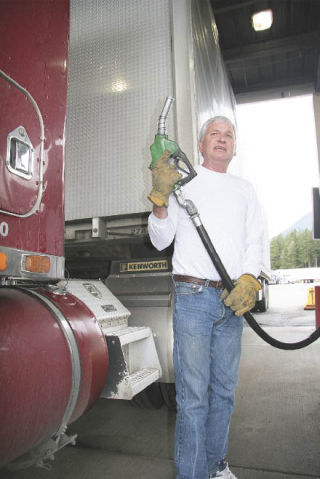

Stopped for refueling at Truck Town in North Bend, trucker Paul Sporcic watched as the dial hit $598. With 116 gallons in his tank, Sporcic shut off the pump and replaced the nozzle after only filling his tank about halfway.

“I can’t afford to fill up in this state,” said Sporcic, who was among truckers stopped in the Valley last week who complained that the high cost of gasoline is driving them out of business.

“This is about as high as I’ve ever paid,” said Sporcic.

Sporcic was among truckers who staged a “slowdown” during the first week of April, purposefully slowing down or stopping their driving to protest spiking fuel prices and their belief that customers and shippers aren’t paying their share of the rising cost of doing business.

Soaring costs

“We’re in bad trouble,” said Florida-based independent operator Charles Russell, 45, who filled up Wednesday, April 9, at Truck Town. “We’re losing money; we’re not able to pay our bills anymore. The fuel is just too high.”

“The customer, the shipper, is not taking the blunt force of it,” Russell said. “It’s just like inflation: the price has to go up. But right now, the truckers are taking all the heat.”

Fuel-saving measures are affecting Russell’s bottom line, and his comfort. Some companies won’t allow trucks to idle anymore, while some trucks have engine governors that keep trucks from going high speeds to save fuel.

“All trucks are governed three miles per hour slower than they were just two or three months ago,” Russell said.

“In a big truck, when you’re loaded, like I am, you have to roll. Rolling means getting up speed going downhill, so you’re at a better speed at the start of the hill.” Low-governed engines mean truckers like Russell can’t “roll.”

“During the summer, when you don’t idle one of these things, you don’t stay cool,” Russell said. “That doesn’t work in 100 degree weather. You’re hot as heck.”

Slowdown

In the recent slowdown, “We all were supposed to shut down, every one of us,” Russell said. “Some did. Somebody like me, I can’t do that.”

With a mother to support, “I’ve got to keep rolling, no matter what,” Russell said. “I’ve got too much at stake.”

Not every trucker is economically able to stop trucking for a day. The business is based on planning trips to arrive on time, and every mile and minute counts. Russell said he has to log thousands of miles a week to make ends meet, and his take-home pay has fallen by hundreds of dollars.

“We’re not making it anymore,” Russell said. “A lot of these operators are pulling out. The new kids aren’t sure what they’re getting into. They’ll roll for two or three weeks, and then they quit.”

While North Bend’s Truck Town hasn’t experienced any uprisings by truckers, Dennis Kohl, store and fuel manager at TA Travel Center at Truck Town, has noticed that independent owner-operators aren’t driving as much as they used to.

“It’s affected everybody,” Kohl said. “I don’t think anybody’s unscathed from this thing.”

If truckers organize a longer-term slowdown, “you’re going to see price increases on everything. You’ll notice it at the grocery stores and everywhere else.”

The price of fuel, Kohl said, affects his business, too.

“At $111 a barrel, we’re not going gangbusters, either,” he said. “The cost of fuel is skyrocketing for us, too.”

Ripple effect

The transportation industry is one of the largest industries in the world, and itruckers say that if they get organized, they could send a powerful message.

“If the trucking industry were to shut down for one day, we’re going to send a ripple through this whole country,” Russell said.

If truckers stayed home en masse for several days or more, “there’ll be a lot of hungry people,” Sporcic said.

“Can you name something that you can get in the store that didn’t come on a truck?” asked Oregon-based truck driver Danny Griffith. “There’s no railroad headed to the stores or the malls, is there? A truck had to bring it.”

“If things continue the way they are, I don’t think it’ll be a slowdown for a day; I think it’s going to cause everybody to shut down indefinitely because they can’t keep going,” Griffith added. “A slowdown is not the answer; a strike is not the answer. That just makes people mad. If you’re out there trying to get somewhere you’ve got to be and there’s a bunch of trucks in your way and they’re slowing way down, that doesn’t make you sympathetic to their cause.

“It doesn’t matter how much I love my truck [or if] I’ve got the American dream of owning my own business,” Griffith said, “if I can’t put fuel in it, and I can’t maintain the equipment.

“If things keep going like this, probably within a month or so, there’s just not going to be enough money for me to operate,” Griffith said. “I can’t spend the money toward tires, and grease, and any kind of maintenance on the truck, because there’s no money left over for that. Tax, insurance, payments. And then somewhere in there, you’ve gotta buy food. It’ll be interesting in another month or so.”

Even after the slowdown, “We still didn’t get heard,” said Russell.

“I stopped my truck for a week,” Sporcic said. “It wasn’t enough.”

But truckers aren’t like the average, homebound citizen, Russell said: Drivers from all corners of the nation stay in constant touch on CB radio.

“When we pass, we hear each other on the radio,” he said. “We’re gaining information all the time.”

Big trucking companies, Russell said, understand the industry and are doing what they can to make changes.

“But it’s all coming downhill to us,” the truck driver said. “We’re the ones that make it go.”