When Puyallap tribal member Carolyn DeFord’s mother, Leona LeClair Kinsey, went missing in 1999, DeFord was at a loss for how to find her. A lack of guidelines or resources to help native communities document information on missing and murdered individuals made it difficult for her to track down clues on her mother’s disappearance. “A lot of rumors have flown around and until we can either find her or find evidence linking somebody to her, it’s just speculation,” DeFord told Seattle Weekly in a January interview.

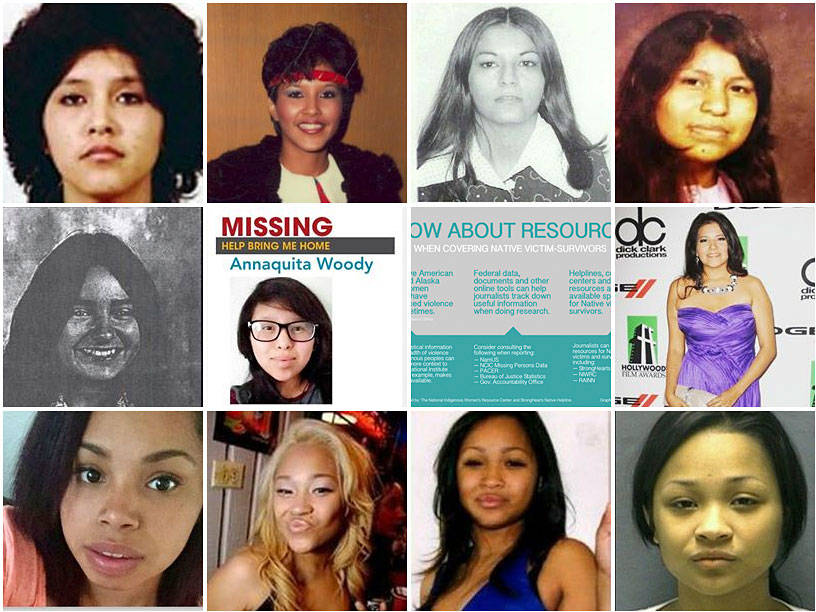

Her whereabouts still unknown, Kinsey remains one of the more than 500 missing and murdered urban indigenous women and girls nationwide, according to a recent study conducted by Seattle-based Urban Indian Health Institute. However, the authors of the UIHI report that looked at cases in 71 cities cited the count as likely underestimated due to poor reporting methods in urban areas. DeFord said she would like to believe that more robust data collection and the creation of protocols to help native families whose loved ones have gone missing would have helped her during her mother’s search.

This congressional session, U.S. Senators are stepping up efforts to address the epidemic of missing and murdered indigenous women through the introduction of legislation designed to enhance record keeping, create law enforcement protocols, and provide crime victim services to native communities.

One such measure includes Savanna’s Act, which was introduced by U.S. Sens. Maria Cantwell (D-WA), Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV), and Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) on Jan. 28. It is designed to address the scant recording of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls. Named after Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, a member of the Spirit Lake Tribe who went missing during her pregnancy in 2017 and was later found dead in a river, the act seeks to improve tribal access to federal crime databases. One provision would require the Attorney General to provide training to law enforcement on recording the tribal enrollment or affiliation of native victims, as well as consulting tribes on ways to improve database access. It would also require standards for collecting data on missing and murdered natives, and protocol on conducting searches for missing people on tribal land. Guidelines would also be created regarding the inter-jurisdictional collaboration between local, tribal, federal, and state law enforcement agencies. Under the legislation, an annual Indian Country Investigations and Prosecutions report issued to Congress would include statistics on the missing natives in the U.S.

“We can no longer sweep these statistics under the rug,” Sen. Cantwell said in a press release. “It’s time to pass this legislation and get it on the president’s desk.”

Savanna’s Act was introduced last Congress, but ultimately didn’t pass the House of Representatives. The re-introduction of the legislation followed the Washington state Senate House Bill 2951, which became law last June and is also designed to bolster data collection of missing and murdered indigenous women. Strengthening recording and response-effort guidelines is especially necessary in Washington, according to the 2018 UIHI report, which revealed that Washington holds the second highest number of missing and murdered urban native women in the nation with 71 cases.

Aren Sparck, government affairs officer for Seattle Indian Health Board, hopes that national and state measures will consult with native-led agencies such as the UIHI and the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board to create “culturally attuned protocols when working with tribes” on data collection.

“The difference in the bills is that the state bill is focused on the systemic problems we have in the state of Washington to uncover the institutional barriers that exist and have allowed MMIWG (Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls) to proliferate in the state,” Sparck said. “The federal bill aims to create, under the direction of the Attorney General, a review of data collection and reporting on MMIWG, and then to create a reporting system that creates preferential funding to those agencies that follow what we hope are culturally attuned data collection and reporting methodologies. The methodologies do not exist yet, and will be created through an advisory group of tribal and federal entities.”

Sparck also highlighted the need to enhance the infrastructure of some tribal and municipal law enforcement agencies that may not be equipped to handle the task of collecting additional data. It’s an ask that would likely require investments in additional personnel, training, technical assistance, and more office space. “If there is preferential funding created out of compliance, we may be moving backward if we do not create a system where smaller law enforcement entities are able to participate from the get go as well,” Sparck said.

Another measure coursing through Congress would provide some additional funding to native victims. A day after Savanna’s Act was reintroduced, the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs passed legislation Jan. 29 to provide resources to native communities. The Securing Urgent Resources Vital to Indian Victim Empowerment (SURVIVE) Act also introduced by Sen. Cantwell would dedicate 5 percent of funding from Crime Victims Fund to Native Tribes. Native communities throughout the nation would be able to apply for victim assistance program funding that would be used at the grantees’ discretion.

“Individuals on tribal lands experience high rates of domestic and sexual violence,” Cantwell said in a press release, “and resources from the Crime Victims Fund are critical in addressing tribal victims’ needs.”