Awesome ‘bot is strutting its stuff on a rainy Monday afternoon in an Opstad Elementary art room.

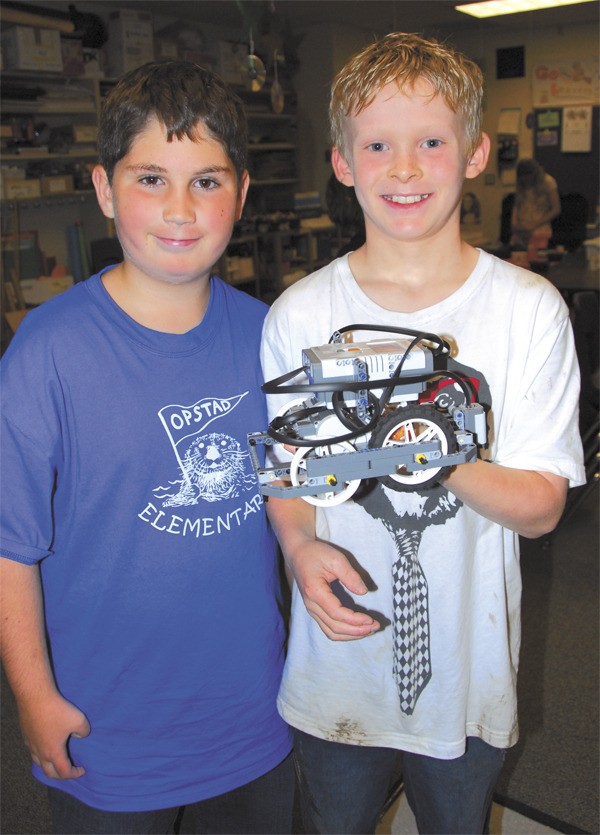

While student Nicolas Puntillo points to a spot on the floor, the kitten-sized robot rolls forward and back by the same measurements and angles that Puntillo and Murphy McDowell, fellow fifth grader and co-creator, programmed into it for a demonstration.

OK, the robot didn’t perform to exact specifications, but it did accomplish its main goal, to serve as inspiration for the rest of the students in the Otterbots club that North Bend parent Paul Sprouse and Snoqualmie Elementary School teacher Rene Peterson supervise.

“We’re only going to make three of them,” said McDowell, who named the robot, after it won a series of performance trials and was selected as the prototype robot for the club.

Puntillo notes that they’ve already enhanced their creation with various attachments for different tasks it can perform, but “We had to take it all off, to show everyone what they’re trying to build.”

Everyone in the room is working on the robots, but only a few are actually focused on assembly. A group of third graders, the youngest age group that can be part of this program, are spinning wheels as they choose parts to duplicate Awesome ‘bot, while Puntillo, McDowell and a handful of others are assembling a model of the arena in which their robots will compete soon. Ryo Karr is roaming the room, filming all the activity, and Mary Jo Mobley is heads-down on a laptop, intently researching the food chain.

How Americans get their food is the subject of this year’s US First (www.usfirst.org) robotics challenge, which the Otterbots club will compete in this Saturday, Dec. 3. It’s a nationwide challenge put forth by inventor and US First founder Dean Kamen. Sprouse, who started Otterbots simply as an after-school program, decided that this year his group could take up that challenge.

For “The Food Factor” competition, the Otterbots are creating robots to complete tasks related to food production and delivery, in competition with other area clubs. Their arena, a replica of the competition’s, is a four-foot by eight-foot surface divided into sections for farm, factory and warehouse, with a few obstacles, like toy cows and pigs, thrown in, just for fun.

Getting the robots to navigate all those obstacles is where the programming comes in. The students haven’t taken any programming classes, so Sprouse introduces them to the concept with “pseudo-code.”

“Pseudo-code is technically what we’re going to make the robot do,” explained Puntillo.

The code is a list of instructions for the robot. Students follow the instructions themselves, and highlight the bugs in the “code” when, for example, they walk into a wall because the code didn’t say when to stop, or they spin in endless circles because the code doesn’t specify how far to the right to turn.

When they find the problems, they have to fix them, too.

“They make all the decisions,” said Sprouse. “We’re just coaching. I can’t tell them what to do.”

Today, the students don’t seem to need a lot of coaching, except for the occasional “did you read in the book about the chickens and the corn?” Based on one of Sprouse’s experiments with his own kids, though, the students will probably need more guidance in the programming phase.

Karr swaps out his malfunctioning video camera for Sprouse’s phone, and explains, “Everybody kind of has their own job.”

Karr is shooting and producing the video that will be part of the club’s presentation, along with Mobley’s presentation, and the three robots’ trials performances. He also influenced the team’s choice of theme, a focus on one of his allergy triggers.

“We’re doing the life of peanut butter,” Puntillo said, explaining the project. “But they’re Legos, so you can’t actually eat anything.”

Lego is the manufacturer of the robot kits that the Opstad students are using, and a longtime favorite of Sprouse’s. He estimates he started the club about four years ago, as an after-school program at Opstad, and “We’ve just had phenomenal success with this.”

Starting with Lego We Do kits, Sprouse expanded to three different classes and kits. With a $900 grant, the small fee charged to club members, and his own money, he’s acquired seven laptop computers and the program software, plus dozens of kits. “You should see my house,” he jokes. “I’ve got the coolest Lego set of anyone I know.”

Right now, Sprouse is hauling his Legos back and forth to school for the twice-weekly meetings of the club, but he has big goals for his little Otterbots program, not least of which is getting a dedicated space at the school. He really wants to see robotics introduced into all of the elementary schools, “so when they get to the high school, they won’t start from zero,” and hopes to enter other competitions for space-exploring robots.

Mainly, though, he wants the opportunities for his students. “Last I heard, there’s something like $17 million available in scholarships just for people who do this kind of thing,” he said. “This is something that kids can put on their resumes even after one year of doing it.”

For more information, visit www.otterbots.org.