When North Bend city employees decided to tear down a tree to make room for a new signal pole at the intersection of Park Street and Bendigo Boulevard, they came across a big, buzzing obstacle: About 25,000 bees had made the tree their home.

Aware that honeybee populations worldwide are dwindling from a mysterious “Colony Collapse Disorder,” the city decided to call a beekeeper to protect the insects.

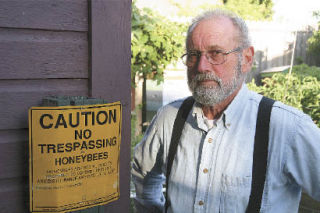

Enter Jerry Mixon, a.k.a. “the bee guy.” He’s been responding to swarm calls for about a decade, removing honeybees at no charge and relocating them to his backyard in Seattle.

On July 9, Mixon, clad in a white suit, gloves and mask, got to work on the tree, which the city had taped off to protect curious passersby.

First, he widened a natural cavity in the tree, creating a hole large enough to fit his hand through to grab the honey comb. As he pulled out each piece, he used a gentle vacuum of his own design to suck up the bees, shooting them into five-gallon water bottles customized with netting. Mixon filled up two and a half of those bottles with bees, then cleared up the air around the tree using a butterfly net. The process took about two hours, and yielded three big buckets of comb.

“It was a huge comb,” he said. “They’d been there for a while.”

The North Bend colony has since joined about 125,000 other bees in the apiary Mixon and his wife, Dawn, maintain behind their home in Seattle’s Wedgwood neighborhood.

Free to relocate whenever they want, the bees will stay there as long as they’re comfortable, Mixon said.

For now, they’re busy bringing in nectar from nearby plants and filling boxes with honey, which they’re saving up for the cold winter months, when they’ll stay inside the hive. As they build up their reserves, Mixon judges how much comb will be surplus. After he “steals” the excess comb, Mixon drops it in a centrifuge machine to extract the pure honey, which he and his wife bottle and sell under the label “Beauty and the Bees.”

Beekeeping is much more a hobby than a business for Mixon, who is retired after working as a teacher, potato farmer and anthropologist. Inside his living room, a glass-enclosed comb provides endless entertainment observing the workers, guards and queen. He says he’s learned more simply watching the bees than he has reading countless books about them. Mixon can talk bees for hours, and the factual errors depicted in Jerry Seinfeld’s “Bee Movie” get him a little riled up. Particularly offensive is Seinfeld’s giving voice to a worker bee, when the foragers are all actually females.

“It’s the worst collection of misinformation I’ve ever seen,” he said of the film. “If you’re going to have a great vehicle like a movie that’s going to fascinate children, they could have done it entirely accurately, and it would have been a fascinating story.”

More concerning, though, is the real-life mystery malady that has been killing off honeybees globally for a couple of years. Bees have always been subject to diseases and mites, and Mixon typically loses about 20 percent of his population each year.

On the East Coast, though, they’ve have been disappearing at alarming rates, with some keepers losing more than half their bees over the last couple of winters. Back at the hives, there’s no shortage of food, and no bee corpses to be found. Researchers haven’t been able to figure out what’s going on.

“Is it nutrition, stress, a virus? We’re still waiting for the final word on this,” said Mixon, who has lost a couple of colonies to the disorder.

On a sunny summer afternoon, though, Mixon’s bees, including the North Bend insects, looked healthy as they zoomed in and out of their new hives, keeping busy as . . . well, you know.