Life might have led to bigger things for 17-year-old Tod Berkebile. The Valley teen dreamed of becoming an engineer, or pursuing a horticulture degree and nurturing his love of plants.

Instead, the Mount Si student was gunned down in the autumn of his senior year of high school.

Berkebile’s killer was never brought to trial. While King County Sheriff’s Deputies zeroed in on at least one prime suspect, there was never enough evidence to bring a murder charge to court. Two decades later, his family waits for justice.

But justice may be closer than ever for Berkebile, whose death is one of five cases in the Snoqualmie Valley being examined by the sheriff’s recently created cold case squad. Besides Berkebile’s death, four other murders have been labeled by deputies as having a high likelihood of being solved.

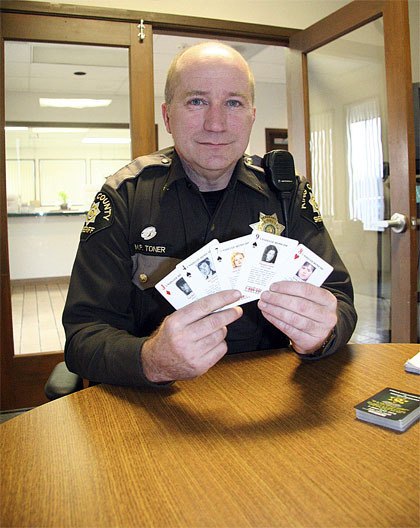

Before assuming duties as current North Bend Police Chief, Sheriff’s Sgt. Mark Toner found a $500,000 grant from the National Institute of Justice to form the cold case unit. Before grant funds run out in May, the unit hopes to solve as many of the 200-plus unsolved mysteries in the county as possible.

At his Boalch Avenue office, Toner opened a deck of 52 playing cards. On each card is the name and photo of a missing person or unsolved murder victim. The cards represent the county’s most promising cases.

“They’re on the deck because there’s still interest in them,” Toner said. “There’s still hope that we can solve them.”

The decks aren’t shuffled by just anyone.

“We pass these cards out at jails and prisons,” Toner said. “It’s a captive audience.”

Convicts play with the decks, read the stories, see the victims — and sometimes turn informant.

The handful of convicts who know something about the cases may share it for a $1,000 reward, for privileges such as a shorter sentence or more comfortable jail cell. To make a deal, information needs to be special and useful. Detectives also have to have a way of corroborating what inmates tell them.

“We don’t give anything away for free,” cold case Det. Jake Pavlovich said.

Long wait

Last year, 250 people were reported missing in King County. Most turn up — they simply never told families where they were going. But some people are never found.

Along with unsolved homicides, the cold case squad seeks those long missing.

In the cold case unit office at the county’s Regional Justice Center, case files — individual stories — can fill as many as 10 binders. The oldest case dates back to the 1940s.

Collecting information and chasing leads take years, even decades. But new technology, such as DNA analysis or recent fingerprinting techniques, have opened up new avenues for solving crimes.

A case is considered solved when the courts say it is — “We’re done when it’s adjudicated,” Toner said.

But the waiting game can frustrate and anger victim’s families.

“Sometimes they get mad at us — ‘You’re not working my case,’” Toner said. “Actually, we are. We may not have got anything on this case for five years. But the door is still open, waiting for something.”

When the cold case unit runs out of funding this May, its three staffers will return to the sheriff’s major crimes unit. From then on, officers will work on cold cases when there is time.

Until then, “we’re trying to review as many as possible,” Pavlovich said.

Unsolved cases

Over the last 30 years, killers have used the Valley’s lonely roads as a dumping ground for their victim’s bodies. Four of the five local unsolved mysteries involved unknown murderers who picked up victims elsewhere but disposed of their victims here.

“It was a remote area, easily accessible,” Pavlovich said. “There were plenty of side roads to go down and get rid of a body.”

Several of the victims were linked with prostitution, and one may have had mafia ties.

In July of 1980, Margaret Earle was found shot to death in North Bend. Earle was a prostitute from Portland, Ore. Detectives came up with at least one suspect, but are still seeking more information to solidify the case.

A decade later, two prostitutes were killed within a year of each other.

Sara Habakangas

Sara Habakangas, a blonde, 17-year-old Virginia teen, had only lived in the Seattle area for a few months when she was found near North Bend, strangled to death, on Nov. 5, 1991.

Habakangas was last seen alive at the Three Bears Motel at South 216th and Pacific Highway South in Des Moines, Wash. Her body was found in a ditch beside a Forest Service Road off Interstate 90’s exit 38.

Media reports from that fall stated that officers linked fingerprints from the body with those of a woman they had arrested for prostitution under the name Jessica Briggs. Habakangas’ true identity was revealed after Briggs’ booking photo was publicized after the murder.

A Valley Record story noted that Habakangas used another alias, Michelle R. Johnson. She was described as about five feet, one inch tall, with two dark tattoos on her wrists and hands.

Officials noted similarities between Habakangas’ death and those attributed to the Green River Killer, Gary Ridgway. However, police have since ruled out Ridgway as a suspect.

Rex Parsons

Rex Parsons was a troubled Phoenix businessman who disappeared during a business trip to Seattle on Aug. 24, 1984. His body was found eight months later by a retired police officer who was walking his dog in a wooded area near Snoqualmie.

Police believe Parson’s death was a case of murder for hire. Media reports identified Parsons as a police informant with a long history of fraud in the Southwest, with several cases made off his testimony

That summer, Parsons flew to Seattle to seek a construction loan. He was last seen at Seattle’s Sorrento Hotel. A large amount of cash was found on his body.

Tod’s story

Every year on Nov. 29, the siblings of Tod Berkebile gather at his grave to lay candles and remember his life.

“We make a promise that we have not forgotten him,” said Kim Berkebile, Tod’s older sister, who now lives in Des Moines, Wash.

Tod would have made a great dad, Kim said.

“He had a lot of goals and ambitions,” she said. “He wanted to work for Boeing. I really saw him having a future in flight.”

He and his mother Aloha gardened together, supported the Mount Si High School plant club, and Tod could have made a great garden shop owner, his sister said. He was a hard-working student, and worked full time at the family restaurant.

Tod also had a side his family didn’t know about.

Police believe Tod was selling cocaine in small quantities to acquantances. His involvement in drugs was probably what led to his death on the night of Nov. 29, 1986.

Tod was last seen at a party, and his car was later found in front of the Snoqualmie laundromat. A hiker found Tod’s body shortly after midnight Saturday in the middle of a Weyerhauser logging road near Lake Alice.

Tod died of multiple gunshot wounds to the chest and neck, and examiners placed the time of death around 8 p.m.

Robbery may have been the motive, and detectives believe he knew the identity of his killer. There may have been at least one witness to the murder.

The Berkebile family offered a $1,000 reward for tips leading to a conviction. Kim Berkebile said the reward was never collected and, for all she knows, is still posted through the Crimestoppers program.

Following the initial investigation, officers forwarded a request for charges against their chief suspect, but the county prosecutor declined to file them, citing a lack of evidence.

Asked if she feels justice has been done, Kim answered, “Absolutely not. They’ve celebrated 23 Christmases and birthdays with their families.”

Every two years, Kim contacts the sheriff’s office, checking Tod’s case.

“Now, they’ve got this cold case squad,” she said. “I’m grateful that there will be some action soon. I sure wish it would have happened while my folks were alive. They never got to see justice for their youngest son.”

New technology means that the case may by solved soon, and Kim said she is amazed by the progress that has been made. Still, she hates to get her hopes up that the 23-year quest will finally end, and then be disappointed.

“We’ve been in this position before,” Kim said. “We’re not giving up.”

Tips needed

To help solve cases, Pavlovich asks residents to remember anything they may have heard about the killings. Sometimes, what may seem like a rumor is remarkably close to the truth, he said. He also asks those who knew the victims, but may have never been interviewed by police, to share their stories.

• To share information about an unsolved crime, call the sheriff’s cold case squad at 1 (800) 222-TIPS.