Outside of a thin line of trees, English ivy covers everything along the historic Sycamore Corridor.

Planted by an unwitting gardener three generations ago, the noxious weed has strangled most of the trees beside the lane of giant, gnarled sycamores that mark a last vestige of the old company town of Snoqualmie Falls.

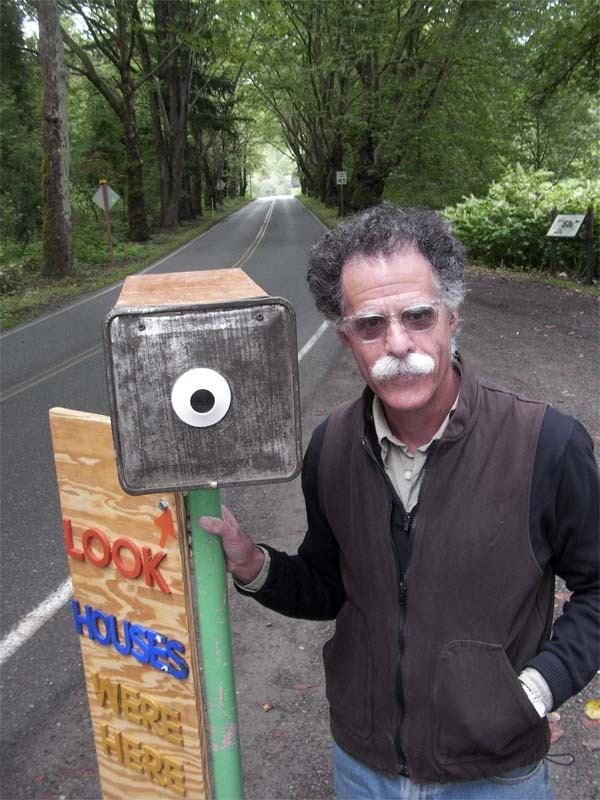

To historians like Fall City public artist Don Fels, history itself is under siege in the corridor.

“It’s being eaten up,” said Fels.

Last month, Fels installed a row of viewing devices, small cones that show views of the corridor, past and present, this summer. The viewers, which included three foot-long, bright-yellow cardboard cones and a more-substantial wood and metal construction, were an addition to Fels’ current exhibit on the lost community of Snoqualmie Falls, on view through October at the Snoqualmie Valley Historical Museum. Both the exhibit and the installation were funded by 4Culture, King County’s heritage arm.

The smaller cones showed how ivy has transformed the landscape along Reinig Road, a rural road that was once a suburban neighborhood called Riverside. His largest viewer shows how the scene looked during the company town’s heyday in the early 20th century. Snoqualmie Falls vanished altogether by the early ‘80s, but King County declared the leafy corridor an official historic landmark.

Besides showing visitors new vistas, Fels’ viewers were also marked with signs calling attention to invisible legacies.

His largest sign tells passerby, in bright, primary colors, “Look, houses were here.”

“I wanted people to think,” Fels said. “My intention was to add questions. I wasn’t going to get any answers, because I don’t have the answers.”

In his exhibits, Fels explored the meaning behind the company town, a task he suspects is a Valley first.

“Why the town was built?” he asked. “Why was it taken apart? And what do we do when we memorialize something here? There’s no memorial to the town itself, which was here for 50 years. There’s only a memorial to some trees, which are really incidental to the whole issue of why there were houses here.”

Fels wasn’t finished. He planned to post thought-provoking questions on the town and legacy next to the viewers.

“But I never got to that place, because they got destroyed,” he said.

Smashed viewers

Fels’ Reinig Road exhibit itself is now a thing of the past. Two weeks after he installed it, vandals tore down his large viewer and made off with the three smaller ones.

While his outdoor exhibit wasn’t built to last, Fels is mystified about why it was destroyed so quickly.

“I thought the weather would kill them,” he said. Fels built the viewers to last a summer season, but lousy weather delayed installation until August.

Still, he thought, “that’s a couple months they can be up there. A bunch of people travel that road. Maybe they’ll get out,” take a look, and be inspired to visit the museum.

But at least a few passersby didn’t understand the objects. Visiting the site one day, Fels corrected a driver who believed the installation heralded a new housing development.

“She thought houses were going to be built here,” he said.

The vandals didn’t destroy a lot in monetary value, but Fels said he spent many weeks on the project.

“I was really disappointed,” he said. “To destroy the whole thing—why? Did someone want to take the viewers home? Were they upset because I asked about ivy?”

New looks

Fels plans to refurbish his largest viewer and return it to the corridor, helping to promote the ongoing exhibition.

“I would love for people to take a look, just because it asks a lot of questions,” he said. “I want people to be interested.”

Dave Battey, the museum’s unofficial mill town historian, was able to look through Fels’ viewers before they were knocked out.

“To me, it was really valuable stuff,” Battey said. “The houses have been gone for a long time. People lose track of the fact, of why we have this living landmark.”

“It gives people clues,” he added. “The other issue is, what’s native and what isn’t? He asked the question, are sycamores native? What about ivy?”

Fels is fascinated by the what-might-have-beens of the lost town, and what it still represents for the Valley.

“It’s important to know about the past,” he said. “If you don’t know about it, are you going to repeat the mistakes that were already made?”

At Snoqualmie Falls, residents had free heat and electricity, a hospital, a community center, entertainment.

“They had everything,” Fels said. “Everybody walked to work. It was sustainable by today’s standards.”

But by mid-century, company town living wasn’t good enough.

“Everybody wanted to be connected,” he said.

Fels still wonders whether Snoqualmie Falls could have adapted to the new century.

“Almost 50 years later, they built Snoqualmie Ridge,” he said. “People have to drive everywhere. It’s almost the antithesis. You might ask, were no lessons learned from the town? What happened to that model? Did it all just go up in smoke?”

• Snoqualmie Valley Historical Museum’s Snoqualmie Falls exhibit remains on view through October at 320 Bendigo Boulevard S., North Bend. Open hours are 1 to 5 p.m., Thursday through Sunday. Learn more at www.snoqualmievalleymuseum.org.