For pure novelty, few events in North Bend could top the 2013 Blues Walk, held one day after, and just a block or two away from the huge gas explosion that destroyed several buildings. Blues Walk organizer Danny Kolke remembered that many media outlets reporting from the site also reported that the Blues Walk was still on.

It was great advertising, he said, “but seriously, that’s not a strategy,” for marketing this year’s event.

That’s not to say that there are no big pulls for this year’s Blues Walk, starting at 6 p.m. Saturday, Sept. 26, and featuring a downtown full of blues musicians in venues throughout the city. The first highlight is that the Blues Walk is back, after a year-long absence that organizers used to reschedule the related North Bend Jazz Walk, to the spring time slot the blues used to hold.

Then there’s the scale of the thing. New venues are opening up for the blues walk, resulting in more than 100 musicians playing in 32 bands and 23 venues, including for the first time, an outdoor stage.

Big tent

The Blues Pavilion, on Main Avenue at North Bend Way, will actually start the Blues Walk, with early shows by Shades of Blue at 3:30 p.m. and Eastside Jam at 5 p.m.

Kolke has mixed feelings about the new venue; it’s on the schedule, rain or shine.

“Plan A is a tent,” he said, if it’s a beautiful evening, as forecast. If it rains, he said, “Plan B is a bigger tent.”

Inside the tent, Blues Walkers will find a stage and a full schedule, capped off with a short set by Caspian Coberly, a 12-year-old guitar phenomenon, at 9, and a festival-wide jam session hosted by Jeff and the Jet City Fliers at 9:20.

“We have an actual jam stage,” said an excited Marlee Walker, “so the musicians who finish early… can come over and jam with other musicians.”

New blood

Walker, a former blues radio host at KPLU, KMTT, KCMU and KEXP, took over the job of booking the Blues Walk performers from Paul Green, and she’s very pleased with her lineup, especially its diversity.

“I booked about half a dozen or a dozen women,” she said. “I didn’t mean to, but afterwards I looked at it and thought that was great! Women were actually the ones who started the blues, you know… I also accidentally got an Asian, a Latino, and a Native American in the mix.”

Finding musicians, and musicians that other musicians want to hear like the local but little-known Septimus, was no problem for Walker a Seattle native who recalled memories of family trips when “we used to stop and get some sort of chocolate thing in North Bend, on our way to go skiing.” Thinking of another event in the state like the North Bend Blues Walk, though, was tough.

“Nothing comes to mind where they turn the bakery and the bank and the car dealership into blues stages,” she said.

These alternate venues, now fixtures of the Blues Walk, presented challenges, Walker admitted, but nothing she couldn’t sell the performers on.

“The musicians are pros and they know kind of what the deal is,” she said. “They can kind of pare down and become more intimate.”

What’s more, they want to. Walker emphasized the interactivity of the Blues Walk. Musicians are scheduled to play short sets, so that the audience is motivated to visit more venues and see more acts. The performers get to do the same.

“That’s one of the benefits for the musicians. They don’t often get to see each other play,” she said. At the Blues Walk, “the bands are going to be putting together these perfect little 25-minute sets,” she said, and then go see their friends and colleagues perform.

And maybe, at the end of the night, jam with them in the Blues Pavilion.

Big bands

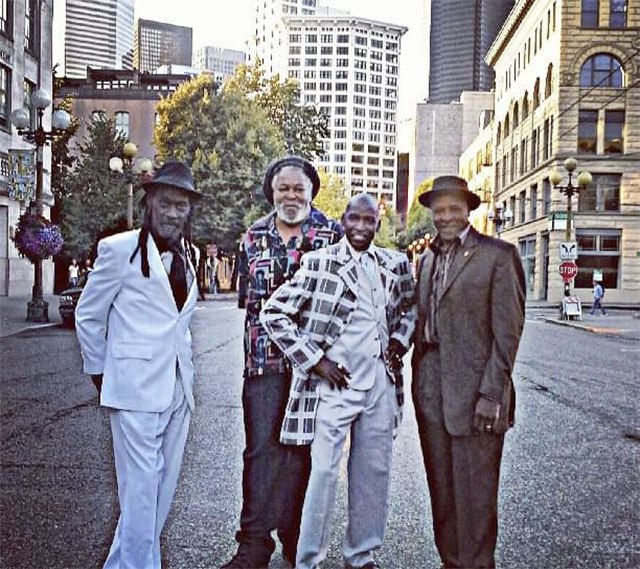

One of those bands, a core quartet of cousins (two sets of brothers) with occasional additions is one of those bands that Walker expects other musicians will want to see.

“They’ve been playing for 60 years, and no one knows about them,” Walker said, despite their claims on several hit songs, lengthy recording careers and mentoring other musicians. “One of them taught Isaac Scott how to play the blues,” Walker said.

Band leader Herman Brown is not troubled with how well-known the band is. “A lot of people that haven’t heard of us, when they hear us for the first time, they generally like what they hear,” he said.

With popular songs like “Mr. Reggae Man,” “I’ll wait for you,” “They call me Junior,” and “Five Minutes to Rock the House,” the band has had a long career writing songs together, and apart, as they pursued their own careers invidually. Herman went to L.A. and joined the Silvers, recording three albums and several national hit songs with the group before moving on to Motown Records and Shalimar.

It was a pretty good career, he said, “but when you put it all together… the lasting thing that I’ve done was my family group, because we’re still together.”

The name comes from the family, too. The men’s grandfather was Septimus Pearl Brown, and he’s the reason they are in Seattle today, although they all came from Arkansas. Septimus, who was not a musician, took a job as a porter on the Great Northern Railroad, and kept an apartment in Seattle, “right at the end of Jackson Street,” Brown said.

As Septimus’ children, the band members’ fathers, got older, the family gradually relocated to Seattle.

Their musical gifts came from Septimus’ brother, Frank, a Delta blues musician very popular in the area where the family lived.

“It’s no wonder that our parents allowed us to be musicians all our lives,” Brown said. “He called himself the boot binder. So it’s probably because of the boot binder that we’re in this mess.”

Septimus is scheduled to play at 9 p.m. at the Sno-Valley Moose Lodge.

For the full schedule and to order tickets — limited to 1,500 — visit http://northbendblueswalk.com.